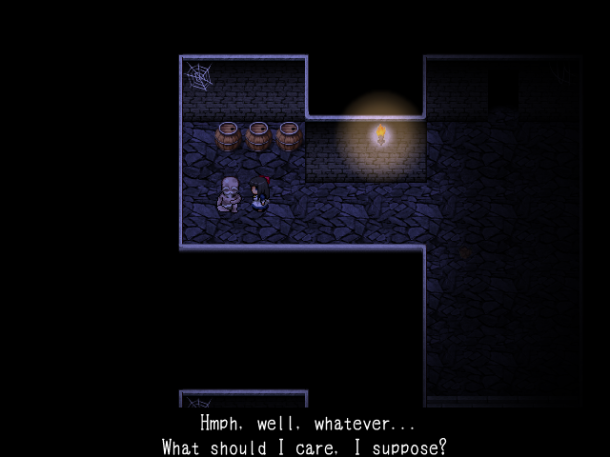

Mad Father is a freeware horror adventure game by Sen, translated from Japanese. The game puts you in the role of Aya, the young daughter of a mad scientist, as a curse re-animates the bodies of her father’s test subjects. In order to save her father’s life, Aya must explore his laboratory and overcome the horrors within, learning the grisly truth about his experiments and his intentions along the way.

It is well worth playing. The dark graphics and the sparse usage of sound contributes to the game’s perfect atmosphere. The game’s puzzles and challenges, while usually not irritatingly challenging, and incredibly varied while relying on a mixture of simple fundamental game mechanics, not unlike Anodyne. More importantly, the puzzles were implemented in such a way that they never broke the immersion and made the game feel unrealistically “game-y;” the gameplay and story are not separate units but are instead intertwined perfectly.

Oh, and what a grotesquely twisted story it is! The game isn’t really about the conflict between Aya and the monsters in the laboratory, nor is that the source of the horror. The real horror of the game is partially the result of the unfaltering love and dedication that Aya and the supporting characters feel toward her father in spite of the atrocities that he commits, and although you know from the onset that he’s doing some pretty monstrous stuff, it gets worse as the game progresses. Moreover, the horror also comes from the realization that Aya is slowly but surely following in her father’s footsteps. In the middle of the game, Aya comes across, and begins to solve puzzles with, a chainsaw, her father’s signature tool of choice, and it all goes downhill from there.

Although the game is fairly linear, there are a few instances of player agency that may result in one of three endings, which makes it an interesting example with which to talk about interactive storytelling. Hold on to that thought, I’ll get back to it in a minute.

As you know, good stories generally require a strong protagonist. This protagonist develops and grows over time, usually to a much greater extent than other characters, and the choices that they make reflect those changes. This poses a great dilemma for telling good stories in games. While the protagonists in games may be actual characters who possess their own motivations, make their own choices, and change over time, at the same time they serve as avatars through which the player acts, a player who has their own separate motivations and who may or may not develop over the course of the game. This makes telling an interactive story with a strong, independent, well-developed protagonist really hard.

Most story-driven games seem to solve this issue in one of two ways: either they make it so that the protagonist is a pure avatar and not a pre-conceived character (the trend Western RPGs), or they make it so that the protagonist is a purely independent character and player agency is introduced only in relatively trivial decision making (the trend JRPGs). For the most part, I find neither solution to be particularly satisfying.

In a game like Mass Effect, the protagonist, Shepherd, being almost a pure avatar, is only compelling because he or she is the way through which we interact with the game world. Besides that, Shepherd is, at the least the way that I’ve been playing her, a really boring character. You see, while most people change and make decisions based on the world around them, my Shepherd made decisions in her world based on my motivations and experiences in my world, based on how I’ve changed. No matter how you play Shepherd, there will always be a disconnect between you and your avatar that makes for a weak protagonist.

That being said, Mass Effect didn’t need to have an interesting protagonist – having a high degree of control over the story through an avatar served as an adequate substitute for having a well-developed hero. However, having an avatar protagonist did limit the sort of story that Mass Effect was able to tell. All of the game’s themes (man vs. machine, etc) and amiable characters (Garrus, etc) were developed around Shepherd, and at best only superficially through him.

On the other end of the spectrum, we have the heroes like Cloud in JRPGs like Final Fantasy 7. Cloud, as boring as he is, does have his own motivations, speak his own mind, make his own choices, and change over time. For the most part, Cloud’s his own man, but he still acts as an avatar in a few limited ways: the player controls his movement, decides who he wants in his party, controls his behavior in combat, and decides what he wants to buy and sell. Although the player also makes some decisions for him that determine with whom he falls in love, for the most part, the choices that the player makes are irrelevant to, or often coincide with, Cloud’s personal motivations. However, excluding player agency from the actual story creates a rift between the story and the gameplay: is Final Fantasy 7 really an interactive story, or is it just a game with a story implemented between the boss fights? What’s the point of telling a story though a game if player agency is irrelevant to the story?

In short, the question I ask is: how does one tell a meaningful interactive story with a well-developed protagonist? Mad Father provides an elegant answer to this question.

For the most part, Mad Father is a linear game with a protagonist whose choices are either independent of or coincide with the player. However, there are two instances of player agency that determine the game’s ending (I’ll try to keep the following discussion spoiler free). The first of them is a choice near the end of the game that the player must make using Aya as their mouthpiece – this is nothing more than using her as an avatar, subverting her own personal motivations, and weakening her character. The second of them, however, is more interesting.

After making the first choice, Aya might have to make another choice to save the life of another character. However, whether she decides to save her or not depends entirely on whether or not she is sympathetic to the character, which is apparently dependent on whether you found and read her diary. So, in this case, player agency is still important (finding the diary), but because Aya herself makes the decision whether or not to save the character, her personal motivations are not undermined. Frankly, I think that this is absolute genius.

So, Mad Father, besides being a highly atmospheric and enjoyable experience, is a game that further demonstrates the potential of interactive storytelling. The game’s writing is mediocre at times, but everything else considered, it’s forgivable and doesn’t make it worth playing any less.You can download it for free here.

Alex writes more about games here.

hkgjgvfgj